REVIEW BY CHARLOTTE FRASER

EDITED BY EMMA PARFITT

An air of softness hums through the Gasworks Studio from the moment the audience begins filing in. A gentle light envelops the space, welcoming and warm. Delicate music drones, disrupted only by the soft chatter and clinking of a few wine glasses. A room full of women – mothers, grandmothers, midwives – all eager to see the action begin. And once it does, we are all swept up in a rich journey of maternity, labour, trauma and comedy.

Citizen Theatre’s Ripening, written and directed by Jayde Kirchert, follows the experience of Lea (Veronica Thomas) as she prepares for the birth of her baby. Lea believes that being a mother and the birth process are going to be incredibly spiritual and transformative experiences for her. This is clear from the very beginning, through a monologue by Lea as she tends to a small tree and speaks to her unborn child of the future she imagines. Watering a tree, the metaphors of fruit, plants, and gardening are introduced, and Lea repeatedly uses the image of a flower to explain the process of birth. A naively picturesque image. She is gentle and sincere in these moments, which continue throughout the play.

Lea’s mother (Ana Mitsikas) brings with her an abundance of questions, worries and judgements about the birth and the choices Lea is making. This is the point where Kirchert’s play begins to articulate how pregnant women are bombarded with well-intentioned criticism and constant unsolicited advice from loved ones, and how at the same time these women’s voices are not being heard. This is continued through Lea’s sister-in-law, Grace (Asha Khamis), entering with a basketful of lemons offering her own advice.

It seems the only place Lea feels heard regarding her wishes for her birth is in her pre-natal birth classes led by Sharon (Emily Carr), a midwife who has seen it all. These scenes confronted, in a highly comedic fashion, the ‘yucky’ or less spiritually fulfilling parts of the birth process. The midwife takes us through the steps of dilation using fruit as a visual marker of each stage – from blueberry all the way to grapefruit. Carr’s performance in these scenes stole the show. The skilful way this character served both as a comedic reprieve and as a support system to the nervous Ali (Asha Khamis), made each of these scenes feel grounded in a soft sense of hope.

This is very violently contrasted with the scenes between Lea and her doctor – cleverly double cast with Ana Mitsikas – in which she is confronted with a web of hospital policy, rules, deadlines and frightening medical fact sheets.

The play is a constant push and pull of power. Of Lea wanting to be listened to and her wishes respected; of the ways in which the medical system fails to properly inform pregnant women around things such as induction; and how, at times, agency is stripped away from women in hospitals during labour. Kirchert’s play taps into an important conversation about how women’s bodies are valued in society. In particular, how pregnancy is perceived and experienced and the effect that adverse experiences during birth can have not only on the mother experiencing them, but their children, and theirs…

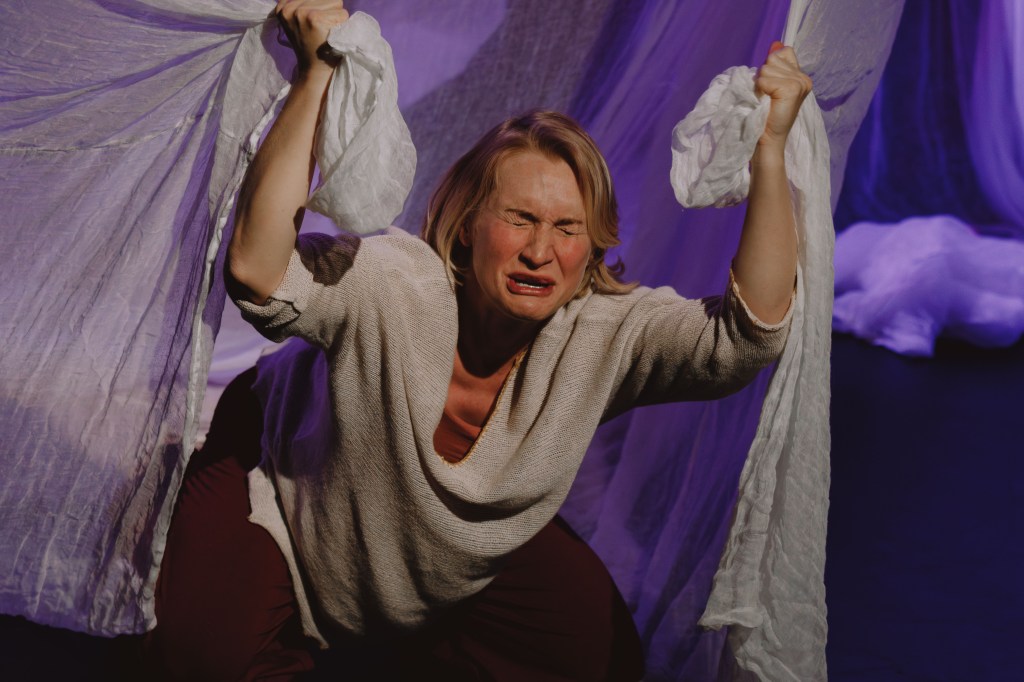

The set, designed by Sarah Tulloch, was made up of long, sheer white curtains that were used in incredibly poignant sequences towards the end of the play. The curtains were able to be twisted and scrunched, punched and tossed to create visuals that added a gut-wrenching intensity to these final sequences. As three generations of women in Lea’s family divulge their experiences with pregnancy and childbirth, the curtains added a visceral visual experience that accompanied the continual stream of intense dialogue. While these drapes added a lot of texture and emotion to these scenes, for the rest of the play I found myself questioning their practicality. They seemed to be difficult to handle at points (especially with set pieces constantly moving on and off and occasionally getting stuck) and a little more practice with handling the curtains may have been beneficial. However, I found the payoff of their inclusion to be impactful. The other major set pieces, a small couch, some chairs, a table and the tree were skilfully utilised in each scene. Despite the small space, the stage never felt crowded or empty, and no set piece was ever needlessly present. The small tree downstage that Lea continuously returned to when delivering her monologues was largely barren but for a few small white flowers. Having this visual of Lea tending to a garden only just beginning to bloom was a beautiful throughline with the fruit and growth metaphors revisited in the play. Tulloch’s set complemented the softness of the play and was visually versatile.

The lighting was a standout in this production. Designed by Clare Springett, from the moment I entered the theatre the lighting cast the stage and the audience in a calm blush. The light pink glow continued through the show, deepening in Lea’s pensive monologues and pulsating through her contractions. It complemented the key themes of femininity and maternity and hit the white drapes in the more intense scenes, accentuating the scrunching and jostling of the fabric. I appreciated how the colour was just as rich and feminine as Lea goes through the intense throes of birth, and moments where she gives over to primal, loud instincts. The coldness of the light in the medical scenes was a sharp contrast to the rest of the show and played into the notion that the healthcare system deals in cold hard fact and policy, not emotion or intuition. The standout moment in the lighting, though, was towards the end when the light focuses behind Lea and gives her angel-like wings – marking the spiritual, transformative force of the birth process. The show had only one blackout, towards the end, and it was masterfully placed. If only it had lasted a little longer so the audience could really sit in the power of the preceding scene. Overall, though, the lighting was consistently precise and smooth, complimenting the set, action, and themes well.

Much like the lighting, the sound design by Imogen Cygler was versatile and impressive. The sound design encompassed everything from a low droning reminiscent of meditation music, to diegetic sounds of hairdryers and water pouring. I found the non-diegetic music to be more impactful on the mood and energy of the play. Every time it appeared I had to actively tune into the sound design and feel what it was doing, because it ran so well underneath each scene. It was well-balanced and provided a strong sensory baseline for the more emotional sequences. I think the play could have benefited from fewer uses of the diegetic sounds, more so when the sound was standing in for something happening onstage – I found the hairdryer when Lea was offstage to be a great use of diegetic sound, for instance – since in such a small space, it is clear to see that whatever the sound is referencing is not actually happening in front of us. Of course, this is a fine line to walk, but since this play does so much to invite us into the world and immerses us so deeply in it, finding the balance of diegetic sound is important. One of the great strengths of the sound design, however, was its ability to work in consonance with the lighting. When the light pulsed, so did the sound. These two design elements propelled us forward in the story and kept the audience grounded in the emotion of each scene.

Costume in this production found strength in its simplicity. The ensemble of actors was small and there were few characters, so the devil was in the details. Aislinn Naughton’s costumes, from the moment the actors stepped onstage, were cohesive, real, and showed necessary attention to detail. Lea, for instance, wore a simple costume that I believed would actually be worn by an expectant mother – her clothes looked comfortable without being boring or plain. Lea’s mother, the doctor, Grace and Ali all had costumes that fit their characters well and had their own little flourishes. I felt as though I were watching real people. My favourite costume had to be Sharon, the midwife. Her beaded glasses chain and brightly patterned shirt, her little ID badge clipped onto her trousers – she looked exactly how I’d imagine a seasoned midwife running birth classes would look. Naughton’s construction of these costumes was well-executed, especially since the cast still managed look like a cohesive group.

The powerful ensemble of four actresses – Thomas, Mitsikas, Carr and Khamis – all offered powerful performances both individually and together. Veronica Thomas as Lea was at her strongest in the heavy emotional scenes, the bickering with her mother, the birth sequence, and the tenser moments in her monologues. A few points at the start I found Lea came across a little ungrounded emotionally, but as the play progressed and the desperation, fear and anger began to creep in – culminating in the explosive contractions and birth sequence – Thomas’s performance revved up and had me hooked. I was invested in Lea’s journey and wanted her to be able to have the experience she wanted, and Thomas portrayed the small fractures of that dream as anxiety began to set in incredibly well.

Similarly, Mitsikas’s portrayal of Lea’s mother and the doctor was striking. Both characters enact different types of pressure on Lea as she comes up to her due date. The mother, well-intentioned but clearly the victim of her society: constantly refusing to divulge much honest information about her own birth experience, while simultaneously questioning Lea over every single choice she made, passing subtle judgement. The doctor, clean and clinical, she doesn’t mince words. Fixed on policy concerns and the ‘rules’ of the system, there is little sympathy or respect for Lea’s wishes in these appointments. Mitsikas flipped between these two extremes with ease and was able to find (very different) moments of comedy in both characters, which was entertaining and admirable.

Another clever double-cast was Asha Khamis as Grace – Lea’s sister-in-law, and Ali – a fellow expectant mother in Lea’s birth classes. Like Mitsikas, Khamis flips between the more upbeat Grace and the nervous but sweet demeanour of Ali masterfully. Khamis, as Grace, plays off of Mitsikas’s mother figure and acts as a well-meaning friend and family member constantly offering Lea unsolicited (at times comically unhinged) advice in the lead up to her birth. The moments between Khamis and Thomas both as Lea/Grace and Lea/Ali were warm, funny and real. The two performers played off each other’s energy beautifully in each of their scenes.

The standout performance for me, though, is Emily Carr as Sharon and the apparition of Lea’s grandmother. Carr commanded the energy not only of the stage but of the entire theatre. She got the audience involved in her birth class presentation, with all of us touching our noses and lips when told to do so and her performance bouncing off the audience’s energy on the fly. When she appeared behind the curtain as the image of Lea’s grandmother, I thought she was a completely different actress, the contrast in her energy and performance was so sharp. Sharon’s character brought not only a large amount of comedy to the show but an important assertion that things like advocacy and emotional state are incredibly important during childbirth.

Kirchert’s work, an original piece self-directed with assistance from Gabrielle Ward, is no small feat. The play is rich with complex emotion and doesn’t shy away from the difficult topics like consent and advocacy. Not only was this play enjoyable, but I walked out feeling like I learned something. About childbirth, about women, about hormones, about strength – Ripening had it all. The play was well paced, and I enjoyed the way it returned to the same few scenes – Lea’s monologues, her mother and Grace intruding on her moments of peace, the birth classes, the doctor – and then was ruptured towards the end by processions of overwhelming information about adverse birth experiences, and Lea’s own labour. I did think that the play didn’t need to return to Lea’s monologues so much — since some of them were so incredibly well-written and emotionally wrought, having fewer may have made them land harder. Additionally, I found the ‘ripening’ metaphor (with the fruit, the tree and, of course, the title) a little heavy handed at times. If this had been woven in a little more subtly, I think it could have been more powerful.

Nevertheless, Kirchert’s play was a tumultuous critique of the healthcare and hospital system and its treatment of pregnant women, as well as a confrontation of wider social norms around pregnancy taboos. Ripening, like an impatient doctor, pokes and prods at the sensitive parts. It pulls pregnancy and motherhood apart like a pomegranate and scrupulously examines each aril, getting its hands stained in the deep emotion of these experiences. An explosive exploration of how strong women are, the play leaves us with a sense of hope and hammers home the importance of being properly informed and listening to your body. Kirchert’s play asserts that knowledge (both medical and intuitive) is power, and sees us out with a gentle, maternal caress that inspires hope and strength in its audience.

Please note that for the purposes of this review, I have referred to ‘pregnant women’ and ‘mothers’ since the play is deeply rooted in not only the physical and biological side of pregnancy but the social experience of women and new mothers, though I acknowledge that there are people biologically capable of pregnancy and birth who do not identify as women or mothers.

Citizen Theatre’s Ripening by Jayde Kirchert played May 28th – 31st at Gasworks Art Park.

CHARLOTTE FRASER (she/her) holds a BA in English and Theatre Studies and is currently undertaking a Masters program at the University of Melbourne. Charlotte is a Melbourne based writer and has previously had creative work featured in Farrago.

EMMA PARFITT (she/her) is the Dialog’s head editor and has written Dialog reviews alongside studying towards her science degree for the past two years. She is a production manager, stage manager and producer on the Melbourne indie theatre scene and a veteran of student theatre at Union House Theatre.

The Dialog is supported by Union House Theatre.