REVIEW BY GRYFF CONNAH

EDITED BY EMMA PARFITT

OCD often manifests as an amorphous, nameless thing. It metastasises in silence, slowly and surely until, one day, its shapelessness is your whole shape and it is staring you in the face from all sides.

I would know; I am living with it.

The experience of OCD (Obsessive Compulsive Disorder) is something that is very difficult to put into words; it is almost impossible to analogise and it defies any good metaphor. Because of this indefinability, I think it is fitting that Victoria Winata’s one-hander bears the title no title. Despite this semantic hurdle, Winata’s production presents a masterful depiction of what it is to live with this neurodivergence. Well, at least in my experience.

We enter the Butterfly Club to find a solemn Tom (Bryan Cooper) ravelling and unravelling a skein of white yarn at a table and chairs. He is looking out blankly beyond the arriving audience: an instantly recognisable and poignant expression to myself and likely others attending that night. Rumination is a core feature of OCD, and it often leaves us feeling vacant and powerless.

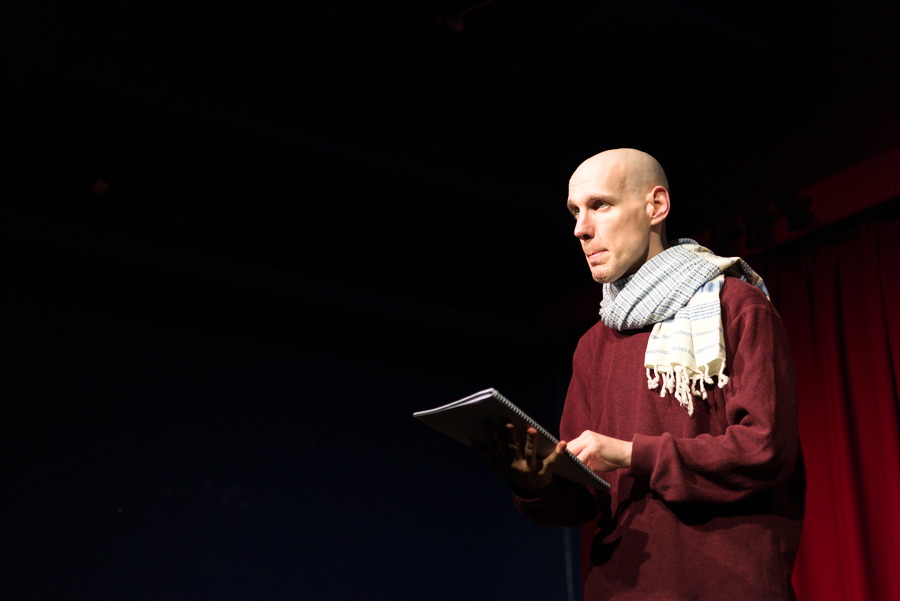

Winata prefaces the reading with a brief explanation of the play’s form and function, describing it eloquently as a ‘reading in motion’ that will be subject to creative development in future months. We are then left in the capable hands of Cooper, as he delivers a performance that will surely, when in full force, be career-defining.

As OCD-experiencer Tom, Cooper welcomes us into his world with vulnerability. We learn that his mother has just passed away, and we are privy to the conversations held between himself, his sister Rebecca and his Aunty Helen in the aftermath of this event. Given that this is a one-man show, these interactions are evoked by skillful tone modulations and physical shifts that render each character perfectly. Rebecca wears a dowdy rust-colored coat, and her vocality takes on a sharper, more whiney quality. Conversely, Aunt Helen dons a diaphanous scarf and indulges in a drawn-out and humorously affected intonation. Cooper utilises a brilliantly nuanced post-sentence grimace to portray Helen’s obvious lack of interest in his own character.

As the story unfolds, we begin to register the ways in which OCD has made its way into Tom’s reality, especially in the wake of his mother’s passing. Significantly, Winata’s script allows us to witness Tom’s first moments of obsession and compulsion, with Cooper narrating flashbacks that examine everything from the counting patterns he uses to self-regulate, to his crippling fear of being a “bad person”. Most interesting to me was Tom’s evident fixation on biblical moralities and specifically the story of Lot and his two daughters, who both court with Lot following the destruction of Sodom in the hopes of repopulating the Earth. In my own experience of OCD, I have found that the categorical evils so often depicted in myths and religious tales are fertile ground for new obsessions and egodystonic thought patterns. After all, the intrusive thoughts that characterise OCD often arise in direct antithesis to your value systems. Winata’s portrayal of this reality was expert and intuitive.

Tom’s moments of analepsis are also significant insofar as they allow Winata to parallel OCD and dementia, which Tom’s mother suffered from before her death. To interweave these two most debilitating conditions is an interesting and compelling authorial choice. Tom recalls how his mother’s diagnosis often made him question his own reality and agonise over the reliability of his memories. The fluid nature of no title’s chronology serves to mirror and magnify this, forcing audiences to sit and wrestle with uncertainty and doubt: cruel fixtures of both disorders.

Although minimal, the production elements employed by Jacques Cooney-Adlard throughout the reading were beautifully effective. There was one point where I had to entirely question whether I was hallucinating the hospital soundscape that filtered over Cooper’s recount of the palliative care ward. The diegetic beeps and clicks were so subtle, gently suggesting their presence as facets of a memory. Similarly, the lighting choices were attuned to the shifts in atmosphere achieved by Cooper. The dimming of the stage in moments of fear, doubt or sorrow was a particularly evocative gesture, and it made for some brilliantly stark stage images.

Complemented by these technical triumphs, the star element of Winata’s invocation was Cooper himself. As someone also living with OCD, Cooper was able to bring an incredible sense of authenticity to the reading. I was enthralled by his performance. From the whispered, harried expletives that so often accompany moments of severe anxiety to the shaking and jittering of hands in moments of crisis, every moment of characterisation was informed and considered. Credit must also be given to Winata, whose own experiences of OCD would likely have served as a strong basis for her direction of Cooper on stage.

I am beyond excited to see where no title is headed. As mentioned by Cooper in the show’s closing statements, it is vital that we share stories of OCD that ‘humanise rather than stigmatise’. It is a condition that is sorely underrepresented and underexplored in today’s theatrical world, and it gives me immense hope to witness productions that treat our neurodivergence with the rigour, sensitivity and candour it deserves. There is no shying away from the ugliness and dysphoria that can stem from OCD in this play, and I praise Winata and Cooper for their unwavering honesty.

Given that this is a work in development, I hope that future iterations of no title see a glimpse of hope baked in. We end with Tom turning around to the knocking of his front door, which he believes to be his sister returning home to remediate a relationship-altering argument. Whilst this final moment implies repair and healing, I was left wanting to see Tom’s character exonerated. I remember the relief I felt upon learning about OCD – it afforded a logical explanation for my thought patterns and absolved me of any guilt surrounding who I thought I was because of these obsessions. I think that foregrounding hope in depictions of OCD is crucial to fostering experiencer empowerment and community morale. This show is definitely on the right track, and I am hotly anticipating how it might cultivate this further!

In all, no title is a brave and vulnerable evocation of the OCD experience, and I feel both honoured and proud to have seen myself reflected on stage. Well done to this production!

no title by Victoria Winata played July 24th-26th at the Butterfly Club.

GRYFF CONNAH (he/him) is an emerging, Naarm-based performer and theatre-maker who is currently studying a BFA in Theatre at VCA. His written, directed and devised works aim to disrupt the inertia that is imposed by capitalist hegemonies, and to explore environmental activism, stories of neurodivergence and disability, and queerness.

EMMA PARFITT (she/her) is the Dialog’s head editor and has written Dialog reviews alongside studying towards her science degree for the past two years. She is a production manager, stage manager and producer on the Melbourne indie theatre scene and a veteran of student theatre at Union House Theatre.

The Dialog is supported by Union House Theatre.