REVIEW BY CHARLOTTE FRASER

EDITED BY MYA HELOU

As the lights dim in the Union Theatre, the audience buzzes and latecomers scurry in, not wanting to miss the beginning of the show. My pen is in my hand, and I flip it between my fingers anxiously – or, perhaps, excitedly (the line between the two is very blurry). I have seen Othello performed before, professional productions and pro-shoots, but this is different. The months of having this day marked on my calendar and the constant stream of content coming out of MUSC’s social media have brought me to the edge of my seat, ready to finally see it all come together. The Acknowledgement of Country plays, and then the captions read ‘ACT I’.

My pen is ready; it is time.

Othello is my favourite of Shakespeare’s tragedies, and, despite its masterful writing and engaging characters, it isn’t performed as regularly as the others. A story of betrayal, love, lies and cunning ruses, the play follows Iago as he enacts his revenge plot against Othello, who has overlooked Iago for a promotion and given the lieutenant position to Michael Cassio instead. Cassio, a man Iago perceives as being completely underqualified for such a post. Enraged by this – and by his suspicion that Othello has slept with his wife – Iago plots to poison Othello’s mind and make him doubt his own wife’s fidelity, implicating Cassio in the process. What results is a tumultuous storm of deception and villainy, still rich with comedy and moments of sweetness and intimacy.

This review will discuss the ending of the play and as such will contain spoilers (but for a play written in 1604 is there really such a thing as spoilers?)

MUSC’s production of Othello (directed by Claudia Scott and Elizabeth Browne, produced by Josh Drake and Tom Worsnop) is unlike any I have encountered before. The first thing I noticed upon entering the theatre was how textured everything was. The set design, masterfully created by Charlene Yong, Hugo Iser-Smith and Max Nania, was rich with detail. Throughout the whole show – all three hours of it – I could always find something new to look at on the set. The small fountain in the centre, the wooden bench with swirling metal details , the black cut outs upstage that mimicked the Venice skyline, and the balcony all filled the stage perfectly. It gave the actors enough space to play with their physicality and still interact with the pieces in meaningful ways. With the leaves carefully wound around the balcony, the fountain, and the fabric drapery on the flats at the back and over the balcony’s archways, the set was rich with texture. As we came out of intermission and the curtains revealed a large white bed, my stomach churned. Something mundane and simple. But the implication that this bed would soon be the site of violence weighed heavy on me. Each set piece was created and arranged cleverly, giving the intensity of the show a soft-landing pad.

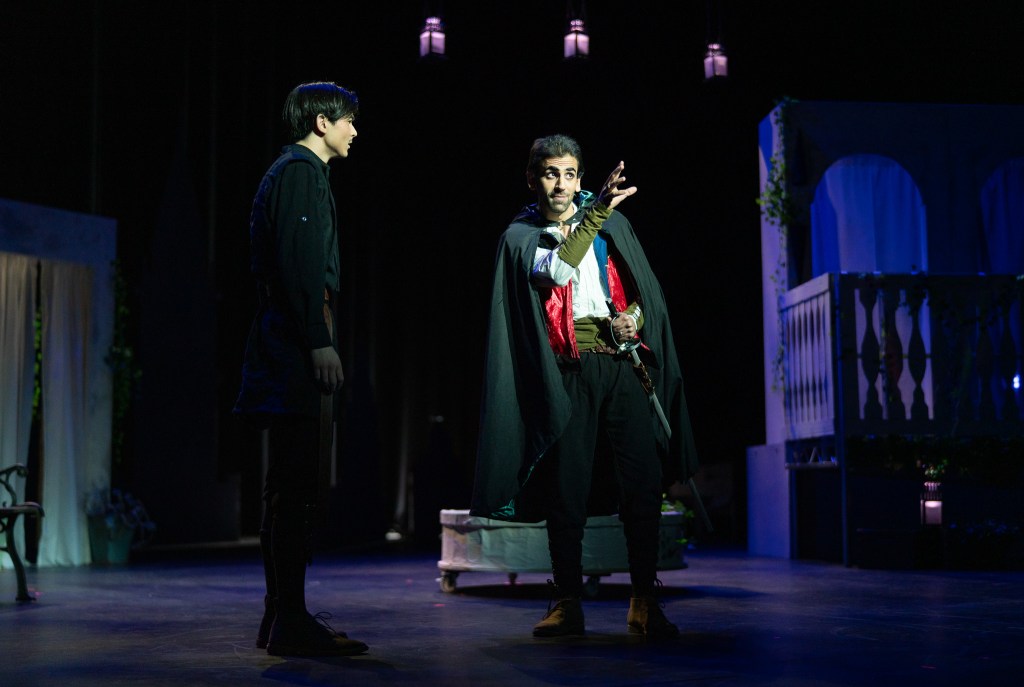

Similarly, the lighting design by Penelope Toong and Iris Donaldson was stunning. Through the entire performance the lighting complimented the action onstage wonderfully. When Iago (Ali Samaei) delivers his first aside to the audience the lights focus downstage, drawing all eyes to him. This became a reoccurring lighting state for Iago’s speeches, and not once did it get old. I found myself constantly trying to work out if the light was just a white light, or if it had a green tinge to it – by the end I still wasn’t sure – because it offered that stark a contrast to the warmer, softer colours that preceded it. As Othello (Akeel Purmunand) and Desdemona’s (Rachel Winterhalter) marriage begins to break beyond repair, all colour drains from the lights, only seeping back in as Emilia (Georgia Campbell) and Desdemona are left alone onstage. The lights shroud them in a warm glow, adding to the sweet, intimate moments they share before tragedy strikes. Each lighting change was purposeful and seamlessly executed.

Perhaps the most show-stopping moment of this production was the scene transition between Act I and Act II. Thunder cracked through the theatre, the lights – mimicking lightning strikes – bounce off the haze, all the while there is a beautifully drawn animation of ships on the ocean playing upstage. It is not hyperbole when I say that it was the best scene transition I have seen in a long time. The animation alone (hand drawn and created by Toong) was an unexpected addition to the show and conveyed the changes in time and space perfectly. The sound in this moment, credit to Dev Mackenzie, was perfectly placed and well-timed. While brief, it was a standout moment for me in the production.

All the technical elements during the performance were smooth and precise, which I’d say is a credit not only to the designers themselves but to the stage managers Nishka Varghese and Dahlia Karam. However, I found the captions provided were – more often than can be ignored – inaccurate to the lines being spoken or the character speaking. It is inevitable that there will be some discrepancy between actors and the captions, however, if captions are being provided as an accessibility tool, it is important that they are as accurate a representation of what is being said onstage as possible. Multiple times throughout the show there were errors and issues with the captions that in the end became frustrating. The rest of the show, however, garners no significant criticism.

A moment of appreciation for Ella Barrett’s costumes. I could potentially write an entire review on the costumes alone. Having followed along on MUSC’s Instagram page I had some idea of what to expect from the costumes, but they were even more fabulous in person and onstage. There was not an element overlooked or a stitch out of place. Barrett, along with Lucy Baker and Rose John, crafted costumes that not only looked incredible onstage, but were intricately detailed and practical: Desdemona’s dress that is able to be taken apart onstage; Emilia’s beautiful green and white gown; Iago, Othello and Cassio’s uniforms, similar enough but each with their own idiosyncrasies that distinguished their characters; Brabantio’s cloak made from a rich purple velvet that came alive under the lights – I could go on forever. I appreciated, as well, that the married women in the play wore their hair up, which showed careful consideration of historical conventions. Everything in Barrett’s costumes had texture: the ribbons and trims, the jewellery, the hairstyles, the undershirts. It was some of the most impressive costume design I’ve seen in a production. Every character had a costume that was cohesive with the rest but still managed to have its own little features that added personality to them. A job incredibly well done.

Under the direction of Claudia Scott and Elizabeth Browne, the team of actors put on rich and nuanced performances. The ensemble performers, Maya June Hall-Davis, Grace Barnes, Ravindi Fernando and Eliška Gidding added to each scene they appeared in. No matter what was happening on stage, every time I looked over to them, they seemed to have their own little scene going on. And these little scenes had their own politics; senators refusing to give each other letters, drinking games and drunk partying, whispering secrets and explanations to one another – there was always something happening between them. And I was thrilled when the clowns appeared! In my notes I’ve written ‘yay clowns!’ at least twice. For those unsure why this is so exciting to me, the clowns are often omitted from productions of Othello, perhaps in an effort not to taint the seriousness of the story. It’s a credit to Scott and Browne’s confidence in their production that this omission was not necessary. They were an incredible inclusion and, while their time onstage was brief, they were one of my favourite parts.

Each of the actors in Othello brought something new and refreshing to their interpretation of the characters. Declan Duffy as Brabantio demonstrated a fantastic command of voice, giving his character a deeper, gravely tone that played nicely into his character’s status, age and emotional state. Kwasi Darko as the Duke of Venice, similarly, commanded the space well, utilising stillness amid a scene where Brabantio shifted around restlessly beside him. Darko and Duffy both later join the ensemble performers (fitting into their little world seamlessly) and were just as entertaining to watch in those moments.

Kailen Missen’s characterisation of Roderigo was unlike any I’d come across before – he leaned into the comedy and dramatics of the character brilliantly. Missen’s Roderigo is a young man hopelessly in love with Desdemona, whose naivety and misplaced trust in Iago is his downfall. Multiple times in the show I wouldn’t notice Missen’s presence onstage until it was his turn to speak – this is a compliment. Roderigo blends into the crowd, bears witness to the turmoil unfolding and is only seen when Iago turns his attention to him. It was an effective, and at times comical, facet of Missen’s performance.

Bianca and Ludovico (Anna Blanch and Dhruv Rao respectively) both enter the action of the play late, but offer nuanced, compelling performances. Blanch as Bianca brought a refreshing depth to the character. She commanded the stage from the moment she stepped out, each stride confident and self-assured, but also brought a vulnerability to Bianca that captivated me. Bianca, who is laughed about by Cassio and used as a pawn by Iago, came across as a real woman just trying to make ends meet. The interpretation and performance by Blanch were careful and considerate. The same is true of Rao’s Ludovico. Coming in at the pointy end of the show, just before disaster and tragedy take hold, Rao’s performance was rich with emotion. I could feel his anger after discovering the fate of Desdemona, Emilia and Roderigo. It was palpable and raw, his eyes wet with tears and voice booming as he sanctions Othello and damns Iago. It was one of the most memorable performances in the show.

Michael Cassio up next. Cassio is a… complicated character. Having been famously portrayed by some of the internet’s favourite heartthrobs like Tom Hiddleston and Jonathan Bailey, I was curious to see the direction Gabriel Jarman was going to take this character. Jarman’s performance can be best described as being a bumbling womanizer – an oxymoron, I know, but it’s true. Jarman offered moments of charm as Cassio interacted with Emilia and Desdemona, but he turned into a bundle of nerves when confronted by Bianca and when being dressed down by Othello. Jarman’s physicality was intriguing and powerful. In Cassio’s famous “reputation, reputation, reputation!” moment, we could feel his anguish through Jarman’s physicality, dropping to the floor and crying out the lines as though he was in pain – all of which was a sharp contrast to his wooing of the soldiers in his first scene. Jarman brought a new version of Cassio to stage, one I felt intense sympathy for, and it was interesting to watch how he breathed relatability into this character by accentuating his flaws.

The titular Othello is a character who is poisoned by the revenge plot being enacted against him – a role that is no easy feat for any performer. Akeel Purmunand’s Othello was agonizing to watch. In the first half, he embodied the doting husband and dutiful general, which made the knowledge of what was to come all the more difficult to confront. From the moment he stepped onstage, Purmunand’s Othello had a firm yet charming air about him. He was very still, a direct contrast to Iago, and his words were calm and assertive. The main challenge of Othello as a character is the degradation from that confident start to the jealous, violent version we see at the end of the show – we have to believe that he is so angry that he would kill Desdemona. Purmunand conveyed this in a believable, nuanced way. The development of Othello was gradual and heart-breaking. From a jovial conversation with Iago where the first seed of doubt is sown, we see a fracture in Purmunand’s Othello. He grows increasingly restless. By the end, gone is the commanding stillness of Act I Othello. Instead, we see a man driven mad with jealousy, his movements erratic and his voice fluctuating between quiet, frantic whispers and loud angry bellows. I found myself constantly eager to see how Purmunand was going to tackle the end of the play, and his performance was eerily book-ended with a return to the more poised stature in the moments before he kills Desdemona – though by then it is tainted by rage, jealousy, and a resignation to his murderous intent.

Purmunand’s counterpart in Rachel Winterhalter’s Desdemona brought a gentleness to an otherwise boisterous and violent play. The power of Winterhalter’s performance was in this softness. She did not fall into the trap of making Desdemona blindly demure and submissive but instead used the sweetness and innocence of the character as the basis of her strength. So often in contemporary media there is an assumption that a strong woman must be independent, outspoken and a bit rough around the edges – Winterhalter’s Desdemona challenges all of that. It is in her soft-spoken words and gentle gestures that she commands power. She captured the audience’s hearts, and the scattered gasps from the people around me who weren’t aware of her fate were a testament to the performance. Starting out very soft-spoken, I was a little sceptical of Winterhalter’s performance, but it grew on me as the play progressed. I had my hand clasped over my mouth at the sound of her cries echoing through the theatre in Desdemona’s final moments. An incredibly moving performance.

‘I am not what I am’ – Ali Samaei as Iago was a refreshing take on this infamous villain, he was sarcastically dutiful, embodying how Iago serves Othello “to serve [his] turn upon him.” One of the first notes I made on this performance and the delivery of Iago’s Act I speech was that Samaei almost made me see Iago’s point. I found myself feeling sympathy for him, I agreed that what had happened to him had been unfair and could completely understand why he had been driven to such villainy. Once his intentions were revealed, they were never too far from the surface. The most impactful way Samaei conveyed this was through a continual fidgeting of his hands, always moving as though he were pulling on a hundred little strings that we couldn’t see. He was wily and cunning and charming in equal measure. His speeches were captivating, and it felt as though he were preaching to us, convincing us of his plan each step of the way – inviting us to celebrate his wins and mourn his losses. It’s a take on Iago I haven’t seen before and one I don’t think I’ll see done as masterfully again.

One of the most interesting parts of this show was how the relationship between Iago and his wife Emilia was portrayed. Where I’ve found this can often be shown as a cold, unloving relationship, Scott and Browne’s production presents us with a couple who seem to be quite loving. Iago and Emilia were always together, and exchanged teasing glances, touches and a kiss – I believed their relationship. It was “bold and saucy”. Emilia rolled her eyes at his teasing, and they held hands or locked arms whenever they stood together. Despite how Emilia reflects on the difficulties in her marriage throughout the play, the relationship presented in this production was one marked by intimacy. In the intermission, knowing the outcome of the play, I found myself wondering where Scott and Browne were taking this relationship – when does the penny drop? And when it finally did, the betrayal ripped through a disbelieving Emilia in a heartbreaking manner.

Georgia Campbell’s Emilia emanated grace from before she even spoke her first line. Opposite Samaei and Winterhalter, she delivered a gut-wrenching performance. From the soft intimacy of her undressing Winterhalter as she sings, to the tear-strained cries moments before her final lines, Campbell’s performance was visceral and enthralling. She brought a softness to Emilia that made the ultimate betrayal all the more painful to watch. I believed that Emilia loved Iago, and the payoff of her repeated, confused cries of “my husband? My husband?” as she held Desdemona’s hand had me biting back tears. She loves him, though perhaps she shouldn’t. She loves Desdemona, and I felt the heartbreak of not only realising the betrayal of her husband, but that she too had inadvertently betrayed the person she cared for the most. Her final defiance of standing up and speaking back to Iago and Othello – not only for her own sake, but for Desdemona’s too – and then echoing the words of Desdemona’s song as she died was the most powerful moment in the show (those tears of mine did fall). Campbell’s Emilia was raw and held nothing back. I hesitate to call it an embodiment of feminine rage – that would be too simple. Campbell embodied the anger, the grief and the love Emilia experiences in a balanced and meticulous way. A performance so intense I couldn’t bring myself to look away.

Violent, raw, textured and enthralling – the list of words I could use to describe this show are in no short supply. MUSC’s Othello is unlike any other production of this play I have seen. Elizabeth Browne and Claudia Scott resuscitate the soul of this play with careful casting and direction, bringing a freshness to this centuries old text that made for three hours of captivating theatre. This production portrayed the themes of love, betrayal, power and deception in a way that was accessible and relevant. The words were spoken with such honesty and skill that everyone could understand them – despite the archaic language. The play was emotionally and visually stunning, a credit to the hard work of all the designers, actors, and production team. Othello is no easy feat, and MUSC has breathed life into it and made it new. Without feeling the need to recontextualise the play into a modern world, Scott and Browne’s production recognises the relevancy of the themes and ideas for a contemporary audience.

The curtains close on the large ensemble of actors, the clapping has only just died down, and my eyes hurt from the tears I’ve shed. I’m staring at my eight pages of scribbled notes wondering where the hell I’m even going to begin writing this review. But I do know one thing – MUSC’s Othello is going to be a tough act to follow.

Melbourne University Shakespeare Company’s Othello played May 8th – 10th at the Union Theatre.

CHARLOTTE FRASER (she/her) holds a BA in English and Theatre Studies and is currently undertaking a Masters program at the University of Melbourne. Charlotte is a Melbourne based writer and has previously had creative work featured in Farrago.

MYA HELOU (they/them) is an English and Theatre Studies major whose love of theatre was fostered by Shakespeare and classical Greek tragedies. They will take every opportunity to discuss either.

The Dialog is supported by Union House Theatre.